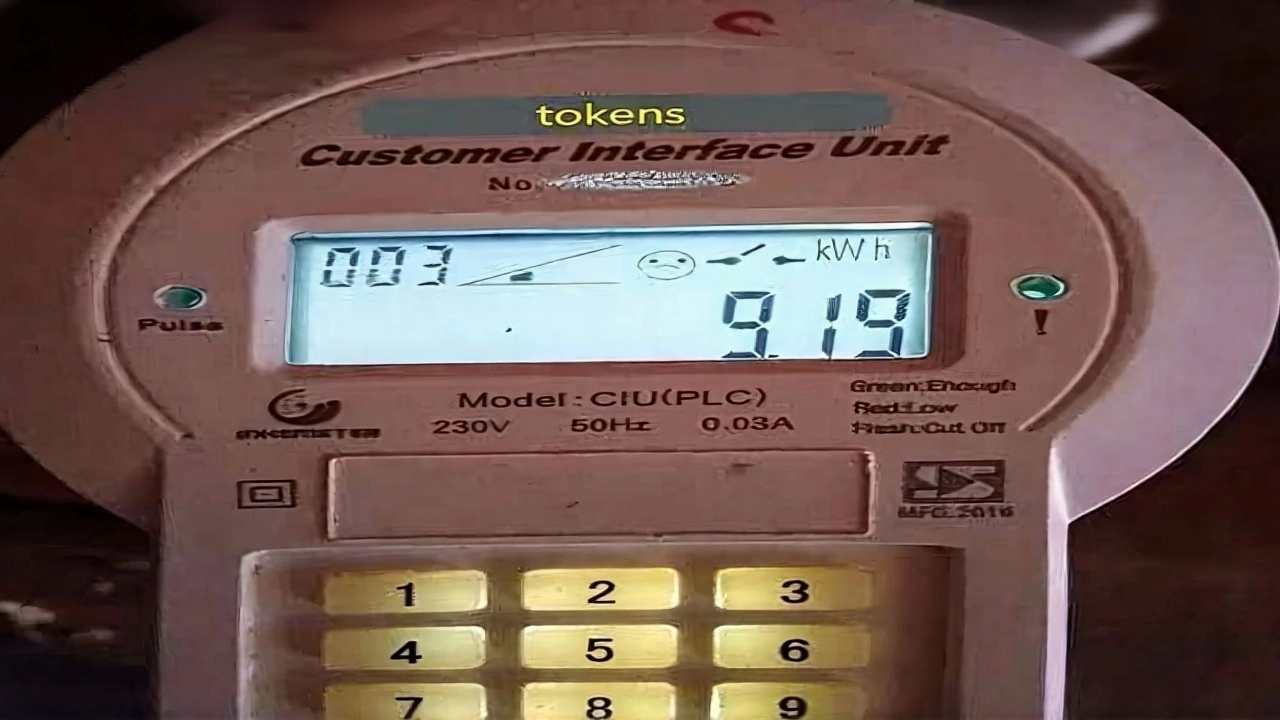

When Rosemary Oduor, General Manager of Commercial Services and Sales of Kenya Power and Lighting Company (KPLC) appeared on The Big Conversation ShowCitizen TV, Nairobi on Thursday night, she finally put a spotlight on a problem that has been buzzing across social media: two customers can pay the same amount for a token and end up with different kilowatt‑hour units. The root cause? A three‑tier tariff system that classifies households by their average monthly consumption, not by the amount they spend on any given day.

How the Three‑Tier Structure Works

KPLC’s tariff framework, launched in 2023, groups domestic users into Domestic Customer One (DC1), Domestic Customer Two (DC2) and Domestic Customer Three (DC3). The categorisation hinges on the average electricity drawn over the previous three billing cycles, a safeguard designed to smooth out one‑off spikes or sudden cuts in usage.

- DC1 – Lifeline Tariff: households that consume fewer than 30 units per month pay Ksh 12.23 – 12.24 per unit (exclusive of VAT, fuel‑cost adjustments and other levies). This is the most subsidised band, aimed at low‑income families.

- DC2 – Mid‑range: customers drawing between 30 and 100 units a month are charged Ksh 16.45 – 16.58 per unit, again before taxes.

- DC3 – High‑usage: any consumer averaging over 100 units (the official ceiling is 15,000 units per billing period) faces a rate of Ksh 19.02 – 20.58 per unit.

Because the rates are set before VAT and the fuel‑energy surcharge, the final amount a consumer sees on a token receipt can look higher, especially for those in DC3. The varying unit‑per‑shilling ratio is what fuels the confusion.

Why Identical Payments Yield Different Units

The crux is that KPLC calculates the per‑unit price based on the tariff band, not the cash value alone. If two neighbours each buy a Sh 500 token, the one in DC1 will receive roughly 40 units, while the DC3 resident may only get about 25 units. Oduor emphasized that the three‑month averaging system prevents a household from being slammed into a higher bracket after a single month of heavy cooking or a festive power‑drain.

“We look at the trend, not the flash‑in‑the‑pan,” she told the audience. “If your average stays under 30 units, you stay on the Lifeline Tariff, even if one month you spend a little more.”

Consumer Reaction and Calls for Transparency

The explanation sparked a flurry of comments on X (formerly Twitter). One user wrote, “They should notify us when we’re about to slip into a higher band – a simple pop‑up on the token receipt would do.” Another suggested a mobile‑app dashboard that shows real‑time average usage and predicts when a tariff shift is imminent.

Consumer advocacy groups, such as the Kenya Consumer Federation, have long urged KPLC to publish an easy‑to‑read chart of the three tiers. The federation’s spokesperson, Abdul Hassan, said, “Transparency builds trust. If people can see where they stand, they’ll adjust habits rather than feel penalised.”

Practical Tips to Stay in the Lower Bracket

KPLC didn’t just lay out the problem; it offered a handful of low‑cost habits to help households keep their average below the 30‑unit threshold.

- Swap incandescent bulbs for LED equivalents – a 9‑watt LED uses a fraction of the power.

- Unplug idle devices (TVs, routers, chargers) instead of leaving them on standby.

- Schedule heavy‑load appliances, such as electric water heaters, for off‑peak hours and avoid running multiple high‑draw devices simultaneously.

- Spread refrigeration usage – keep fridges full but not overloaded, and clean coils regularly.

- Leverage natural light during the day to cut down on lighting needs.

These steps, while simple, can shave a few units off a monthly bill, keeping more families eligible for the lifeline rate.

What Lies Ahead for Kenya Power’s Tariff Policy

Oduor hinted that KPLC is reviewing the possibility of a digital notification system. “We’re piloting SMS alerts for customers whose three‑month average is within five units of the next tier,” she said. If successful, this could become a nation‑wide feature, easing the anxiety that currently fuels online backlash.

Meanwhile, the regulator – the Energy and Petroleum Regulatory Authority (EPRA) – is monitoring the public sentiment. An EPRA spokesperson, Dr. Grace Njeri, remarked, “Tariff transparency is a priority. We expect KPLC to continuously improve communication channels with consumers.”

Overall, the three‑month averaging rule is designed to balance fairness with financial sustainability for the utility. Whether the upcoming digital tools will satisfy the public remains to be seen, but the dialogue is a positive sign that Kenya’s electricity market is moving toward greater openness.

Frequently Asked Questions

How does the three‑month averaging system affect my monthly bill?

KPLC looks at the total units you used over the past three months and divides by three to set your tariff band. This means a single month of high usage won’t instantly push you into a higher‑price category; only sustained changes alter the rate you pay per unit.

What happens if my average usage climbs from DC1 to DC2?

Once your three‑month average exceeds 30 units, KPLC reclassifies you to DC2. Your token purchases will then be calculated at roughly Ksh 16.45‑16.58 per unit, so you’ll receive fewer kilowatt‑hours for the same amount of money.

Can I check my current tariff band before buying a token?

At present, KPLC prints the tariff band on your monthly bill, but not on individual token receipts. The company is testing an SMS alert that will notify customers when they’re close to moving up a tier.

Do taxes and levies significantly change the unit price?

Yes. The rates quoted by KPLC (12.23, 16.45, 19.02 Ksh per unit) are exclusive of VAT, fuel‑energy adjustments and other statutory levies. Adding those can push the effective cost per unit up by 5‑10 %, depending on the current tax rates.

Is the Lifeline Tariff subsidised by the government?

The Lifeline Tariff is part of Kenya’s social protection agenda. It’s funded through cross‑subsidies within KPLC’s overall revenue model, meaning higher‑usage customers indirectly support lower‑usage households.

Anurag Narayan Rai

Reading through the explanation about Kenya Power's three‑tier system feels like opening a textbook on electricity economics, yet the real‑world impact hits home for anyone who has ever bought a Sh 500 token and wondered why the numbers don’t match up. The three‑month averaging rule, as Oduor described, smooths out occasional spikes, which is smart because a single month of heavy cooking shouldn’t permanently push a family into a higher bracket. It also means that households need to think about their consumption habits over a season, not just at the end of the month, which can encourage more sustainable behavior. For low‑income families, staying under the 30‑unit threshold keeps the Lifeline Tariff alive, and that subsidy can be the difference between having light for study time and being in the dark. On the other hand, the mid‑range DC2 band still offers a reasonable rate for families that have grown beyond the bare minimum but haven’t yet reached the high‑usage levels. The high‑usage DC3 tier, while more expensive, reflects the reality that larger homes or businesses need to pay their fair share, and the cross‑subsidy model keeps the system balanced. One thing that stands out is the lack of real‑time feedback; people only find out they’ve shifted bands after the next bill, which can feel unfair. The proposed SMS alerts could close that gap, giving households a heads‑up before they make a big purchase or invite extra guests. Another point worth noting is that taxes and levies can add another 5‑10 % on top of the base rates, so the headline figures Oduor mentioned are just the starting point. The recommendation to replace incandescent bulbs with LEDs is a simple win, cutting down on waste while also preserving those precious units. Unplugging idle devices may sound obvious, but the cumulative effect across a neighbourhood can be substantial, especially when many households are clustered in the same tariff band. Scheduling heavy appliances during off‑peak hours can also help, as the utility often provides lower rates for off‑peak load, though this article focused on the three‑tier structure rather than time‑of‑use pricing. The suggestion to keep fridges well‑maintained is a practical tip that many overlook; a dirty coil can consume up to 30 % more power. Finally, leveraging natural light isn’t just an aesthetic choice-it’s a budget‑friendly strategy that aligns perfectly with the Lifeline Tariff’s goals. In summary, the three‑tier system aims to be fair by looking at trends, not anomalies, and the upcoming digital tools could make it even more transparent, benefiting both the utility and the consumer.

Govind Kumar

Thank you for the thorough exposition; the clarity with which the tariff bands are delineated is commendable. It is evident that the policy seeks to balance equity with fiscal responsibility, particularly through the Lifeline subsidy. The emphasis on a three‑month average rather than a single billing cycle demonstrates a prudent approach to categorisation. I appreciate the inclusion of actionable recommendations, such as LED adoption and unplugging idle devices, as they align with broader energy‑efficiency objectives. The prospective SMS notification system appears to be a constructive step toward heightened transparency. Overall, this communication serves as an informative resource for all stakeholders.

Shubham Abhang

I gotta say, this whole token thing is kinda confusing, you know?, especially when two neighbours buy the same amount, but get different units, it feels unfair,, kinda like the system is playing tricks on us,, maybe if they printed the tariff band on each receipt it'd be easier to understand,, lol,, also, the whole three‑month averaging, is that really needed? seems like a way to hide the real cost,, ah well,, hope the SMS alerts work, because I dont want to be shocked next month,,

Trupti Jain

Honestly, the article does a decent job, but I wish they'd spice it up a bit-maybe throw in some vivid analogies or a dash of satire. The Lifeline Tariff is a lifeline indeed, but the jargon can be a maze for the average citizen. Still, kudos for laying out the tips; swapping bulbs is a no‑brainer, and unplugging chargers? Classic. A bit more flair would elevate the piece from informative to captivating.

deepika balodi

Got it-average usage decides the tier, so keep consumption low for cheaper rates.

Priya Patil

I think the tips are spot‑on. Switching to LEDs can shave off a good chunk of units, and those standby devices are sneaky energy vampires. If more people adopt these habits, the overall demand could drop, which might even influence future tariff revisions. Also, the idea of an SMS alert is great; real‑time info empowers users to adjust before they’re hit with a higher bill.

Rashi Jaiswal

Wow, love the optimism! It’s super encouraging to see KPLC actually listening to us. Those LED bulbs are cheap af and save tons of money, and I’m already unplugging my phone charger when it’s not in use-who knew that tiny habit could matter? The SMS alerts could be a game‑changer, like getting a heads‑up before you’re stuck paying more. Let’s all do our part and keep those units low, fam!

Maneesh Rajput Thakur

People need to understand that the three‑tier system isn’t just a bureaucratic whim; it’s tied to the hidden subsidies that keep the grid afloat. There’s a lot of speculation about who benefits from the cross‑subsidies, and some even suggest that the elite influence the rates to maintain a certain profit margin. While the official line is about fairness, it’s always wise to stay skeptical and demand full transparency on how those funds circulate. Remember, power is power-literally.

ONE AGRI

It really hurts my heart to see families struggle because of a system that seems designed to keep them in the dark-both literally and metaphorically. The three‑tier tariff, on the surface, looks fair, but when you dig deeper, you see that the higher‑usage households are essentially paying for the low‑income ones, which is noble in theory yet burdensome in practice when those households are already grappling with economic hardship. The lack of immediate feedback, like real‑time notifications, feels like an intentional barrier, making it harder for people to adapt their consumption habits proactively. Moreover, the proposed SMS alerts, while a step forward, may not be enough if the underlying structure still favors the wealthy and the powerful. We must demand not just transparency but a re‑evaluation of the subsidy model to ensure that it truly serves those who need it most, without perpetuating a cycle of dependency and disenfranchisement.

Himanshu Sanduja

Great summary.

Kiran Singh

👍 Love the practical tips! Switching to LEDs saved me a few bucks already, and those SMS alerts sound super helpful. Let’s keep that energy-saving vibe going! 🌟

Balaji Srinivasan

These insights are useful, especially the part about averaging consumption over three months.

Hariprasath P

Honestly, these "energy‑saving" tips feel like a pat on the back while the real issue-who's really paying for the subsidies-gets ignored. People keep saying "just unplug your charger," but they forget that many households can't afford LED bulbs in the first place. The system needs a overhaul, not just reminders to turn off lights.

Vibhor Jain

Sarcasm aside, the notion that a three‑month average magically solves all equity concerns is naive; without rigorous oversight, it becomes another tool for managerial complacency.

Rashi Nirmaan

It is imperative that we, as a nation, uphold the sanctity of equitable utility distribution; any deviation from transparent practices undermines our collective progress.